The internationally acclaimed comic author speaks to Nina Bunjevac on the relationship between art and political turmoil, providing an impressive historical tour of Balkan alternative comics. Zograf is truly one of a kind

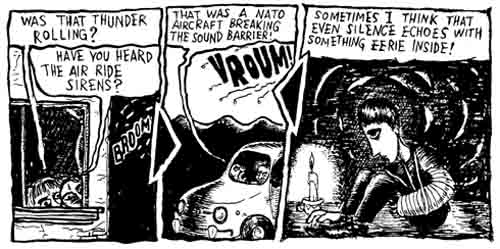

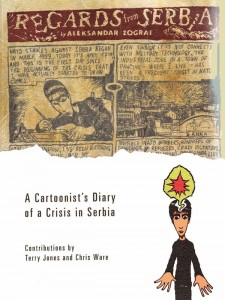

When Aleksandar Zograf’s book Regards from Serbia came out in 2007 with Top Shelf, North American audiences had a chance to witness life in this Balkan country through the eyes of – as Aleksandar refers to himself – a “regular guy”, or “small fry”, confronting the disasters of war and political turmoil.

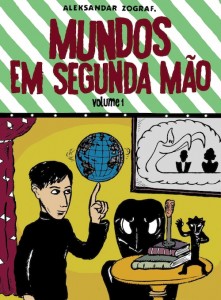

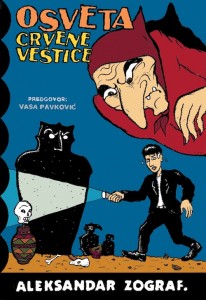

The artistic accomplishments of this highly prolific, yet humble cartoonist can only be surpassed by his contribution to the cultural scene of his home town of Pancevo, located some 17 km northeast of Belgrade – a town he never left behind, in spite of having achieved international success. His latest books to come out with Serbian publishers, Secondhand World and Revenge of the Red Witch are collections of strips originally created for the Serbian weekly magazine Vreme – with subjects ranging from history and archeology, to popular culture and strange flea market acquisitions. So far his Vreme stories has been translated and published in Italy, France, Portugal and Hungary, where they have achieved critical acclaim.

In addition to creating comics you also write articles for local papers and magazines under your given name, Sasa Rakezic. Journalistic influence in your comic strips is undeniable. How did you develop your artistic discipline and what are some of your biggest influences?

Despite my obsessive drive to draw as a child, at first I believed that I was going to be a writer and a journalist. I started to publish my articles for national magazines when I was a teenager. Gradually, I sought to express myself visually, and eventually began to mix visual art with literature, which is basically what comics are.

Despite my obsessive drive to draw as a child, at first I believed that I was going to be a writer and a journalist. I started to publish my articles for national magazines when I was a teenager. Gradually, I sought to express myself visually, and eventually began to mix visual art with literature, which is basically what comics are.

I always read a lot, and this is why I developed into a highly inefficient and confused personality – simply due to my inability to handle the real world. My other interest is dream exploration, which paints a picture of a strange personality of Aleksandar Zograf.

I am aware that I am not clever, and I enjoy laughing at myself. That’s why I believe humor is an important ingredient of “art”. Without humor, everything around us seems so depressive, distant, unintelligible and empty. As if we’ve come into this life in order to complete the same old cycle and then simply vanish, with no deeper meaning applied. As if entire generations of people come and go just in order to repeat this pathetic human destiny. But if you observe it all with humor, if you laugh at this pathetic struggle, suddenly there seem to be a lot more meaning to it, a new perspective of joy and playfulness. I wake up every morning, anticipating this unique drama that is going to be played before me, even in the moment when nothing special happens. And I laugh at it all!

Your book Regards from Serbia was a collection of daily strips created during the 90s. It offered a unique perspective, of a “normal” person or, as you referred to it, a regular guy, or a small fry – living in Serbia during times of war and political oppression. Is this something you intended to do?

When I created these stories, I really didn’t know what the reaction might be upon publication – my only aim was to speak about things that were happening around me. I was lucky that people reacted in positive ways – it’s so easy to form stereotypes about the national and the group identity, especially in times of crisis and war, or during heavy media campaigns. What the Western media were missing during the 90s was the information about the “normal” Serbian people, as the most frequently shown were the Serbian war mongers. The fact was that MOST of the Serbian people were clinched by catastrophic actions taken by their own government on one side, and the mindless actions of NATO who were bombing their towns by using the most advanced weapons on the other. Both seemed unstoppable in their actions, and blood was flowing down the

streets.

So I guess that my work was just a voice of “normality”, a story of a small fry, a regular guy, who watched all this unfold. I didn’t try to categorize Serbs as “good” or “bad” guys; I just communicated my thoughts and musings about the drama of a single soul confronting social disaster of war and political turmoil.

What is the current “scene” like in Serbia?

I guess that it’s not that different than in other countries. Today, there are a number of cartoonists in Serbia who create and publish alternative comics – as elsewhere; it’s a pretty diverse bunch, sometimes with conflicting ideas about the aesthetics and meaning of the medium. Some produce and self-publish while others submit their work to magazines; and then there are those who work as commercial illustrators, designing CD covers, children’s books and what not.

I guess that it’s not that different than in other countries. Today, there are a number of cartoonists in Serbia who create and publish alternative comics – as elsewhere; it’s a pretty diverse bunch, sometimes with conflicting ideas about the aesthetics and meaning of the medium. Some produce and self-publish while others submit their work to magazines; and then there are those who work as commercial illustrators, designing CD covers, children’s books and what not.

Most people from this scene meet at art exhibits, alternative festivals and workshops. One of the greatest things about this scene is that it moves across national borders with a great ease. A lot of Serbian authors publish abroad, and there are foreign artists visiting, even moving here. One of the examples is Johanna Marcade, who moved from France to Serbia, where she lives with Bruno Tolic, a Croatian artist. They are involved in many different projects, including Novo Doba, a comics festival held in Belgrade and Pancevo, and Turbocomix, which is an international AND local publisher. I think that presence of the artists coming from different cultures is of vital importance, since they bring fresh blood and unique perspectives.

It may come to many as a surprise that Serbia, among other ex-Yugoslav republics has a deeply rooted tradition of comics; this is a subject you are particularly well versed in. Could you briefly describe the history of comics in this region, leading up to the war of the 90s, and how has it changed after the decomposition of Yugoslavia?

To speak about vintage Serbian, or ex-Yugoslav comics, is to point to an unsung chapter in the history of European comics. In this predominantly rural country, which was called The Kingdom of Yugoslavia back in the 1930, there were several publishers of comics, with such magazines as Politikin Zabavnik (founded in 1939 and still operating), which had a long standing tradition of publishing American, European, and domestically produced comics. There were several great cartoonists operating in Croatia’s capital Zagreb as well. Perhaps, if it weren’t for such dramatic sociopolitical changes during WWII, a more stable comic book market would have been created, possibly not that different from the major West European markets. Following the stabilization of the post-war period, the publishing of comics had continued, and was blooming by the 1960s. Stripoteka was a magazine based in Novi Sad, dedicated to contemporary comics, especially Franco-Belgian, but not exclusively – they had a big print run, and offered steady employment to some of the cartoonists.

Another catastrophe occurred during the 1990s, after the split of Yugoslavia. Most of the publishers either went bankrupt, or had to change their policies, according to an already diminishing audience. While before the split they were selling comics and books in a country of 20 million inhabitants, after the split the Serbian market (for example) diminished to 7 million, with most of its people living in poverty. Under these circumstances, many of the comic magazines (which were mostly publishing mainstream material) flopped. People who were interested in comics had to create their own small magazines and zines; this actually opened up the way for the more experimental and rebellious forms of expression, not produced for the pleasure and acclaim of wider audiences.

Did the alternative stream of comics emerge at this point?

Self-conscious “alternative” in the field of comics started to emerge in the early 90s, after decomposition of Yugoslavia. This may sound strange – how can any form of art develop under such catastrophic circumstances, such as a seemingly endless series of wars (all lost by the Serbian government under Milosevic’s rule) and enormous economic crisis induced (again) by catastrophic economic policy of the government, the embargo, NATO bombing… Yet it happened, just like that – because some individuals, especially artists, began questioning the values of their society. Mind you, it was during the Vietnam War that the American underground bloomed, marking such questions.

Self-conscious “alternative” in the field of comics started to emerge in the early 90s, after decomposition of Yugoslavia. This may sound strange – how can any form of art develop under such catastrophic circumstances, such as a seemingly endless series of wars (all lost by the Serbian government under Milosevic’s rule) and enormous economic crisis induced (again) by catastrophic economic policy of the government, the embargo, NATO bombing… Yet it happened, just like that – because some individuals, especially artists, began questioning the values of their society. Mind you, it was during the Vietnam War that the American underground bloomed, marking such questions.

During Milosevic’s reign of power an entire independent cultural scene emerged, connected with underground music, literature, art, etc. An independent radio station B92 was a meeting point of many creative and interesting characters. People tried to express dissatisfaction with Milosevic’s rule, and this feeling of rage and hopelessness, exaltation and depression created an atmosphere that lead to an emergence of a lot of non-conformist artists, including the creators of alternative comics.

Did collaborative efforts between cartoonists and editors from the former Yugoslav republics exist during the 90s and how was this affected by the mainstream politics? What was the scene like in other former Yugoslav countries during this time period?

There were, of course, different cases involving different people but, in general,regarding the alternative comics, there were bonds between cartoonists and editors from different ex-Yugoslav republics that were not broken by the war or political crisis. An obvious example is Stripburger from Slovenia, which published a lot of Serbian cartoonists. But you have to be aware of the fact that that the alternative scene consists of artistic, unconventional people, who do not care for the barriers constructed by the mainstream politics anyway!

There were some great things happening in Slovenia, including the above mentioned Stripburger, which is still one of the best comics magazines in Europe; it started in mid 90s and soon grew into an important phenomenon. In the early 90s, the European scene was still pretty conservative, focused on producing expensive albums featuring pretentious stories. With the explosion of smaller and more flexible magazines and zines things began to change gradually. Now we have great artists such as Igor Hofbauer and Komikaze in Croatia, Gorand in Macedonia, Jakob Klemencic in Slovenia etc.

What are you working on now, and what are your future plans?

I continue to produce a two page story for Vreme magazine, every week; it’s a lot of work. I also conduct a little event held a dozen times a year, called GRRR!Program, at a venue called Elektrika in Pancevo. We usually discuss comics and alternative art in general. On the other side, I am frequently travelling abroad to present different editions of my comics, and I use it as an excuse to learn more about other realities.

*More info: www.aleksandarzograf.com