Two decades later, the Yugoslav monument to yesterday’s bright future has become a haven for weed-smoking teenagers and scientists conducting illegal experiments. Now the state wants to rebuild it

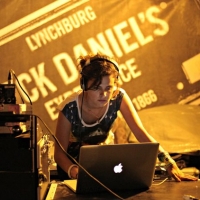

Temporary Viewing Platforms exhibition at the abandoned tech park in 2009 by Milena Putnik / Photo: Ivan Petrovic

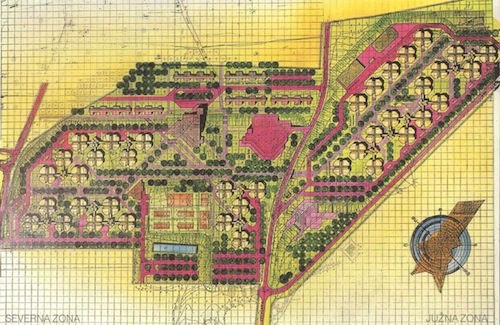

“In two years, Silicon Hill in Zvezdara will be a reality”, Dr. Drasko Milicevic, director of Belgrade’s Mihailo Pupin Institute promised the Yugoslav public in 1989. By the end of that year, the project was shelved. As the country’s economic crisis deepened, it became increasingly clear that the government would be unable to afford the construction of a sprawling, Silicon Valley-style tech park. And so construction was halted, the site abandoned, and instead of a technological park, Dr. Milicevic went on to open a boutique selling women’s stockings.

Meanwhile, the abandoned structures became a monument to failed investment and a bright Yugoslavian future that never quite arrived. The ruins told a different, and perhaps more honest story about the country’s history and dissolution than any government-commissioned monument or war memorial ever could.

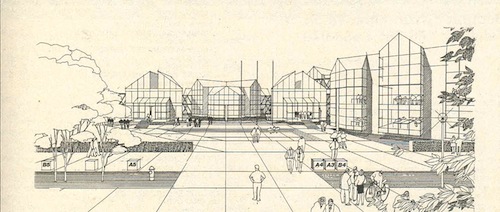

The construction site was opened with the laying of a ceremonial foundation stone in April of 1989, the spring before the Berlin Wall fell. An original brochure published to promote the park is filled with text alluding to the uncertainty of those times, and to Yugoslavia’s ambivalent future. As one italicized passages reads, “for decades we tried to walk a path different from the world’s! Now we must go into the world, and with it!”

Dr. Milicevic’s plan to build a Silicon Valley on the margins of Zvezdara forest was a last ditch effort to save the Yugoslavian economy from ruin. During the 1980s, the situation was dire: workers often went unpaid for months, petrol was the most expensive in Europe and educated young people comprised an absolute majority of the unemployed.

Together, these conditions created considerable push factors for emigration, and many of the country’s most talented young scientists and researchers fled. Dr. Milicevic hoped that the construction of world-class facilities and the creation of hundreds of new jobs would help Yugoslavia retain its brightest young people, as well as lure recent émigrés back home. The project included plans for the construction of 40 research and development buildings and a 300-400 bed hotel. Ultimately, the plan proved too costly, and just two years after the construction site was abandoned, Croatia and Slovenia declared independence, putting the entire Yugoslavian experiment to rest.

Though officially abandoned, the site enjoyed a rather lively existence. During the more than twenty years they sat empty, the unfinished construction drew many curious observers to the edge of Zvezdara forest. Some were attracted to the excellent view offered by the structures’ upper levels. In 2009, local artist Milena Putnik staged an exhibition entitled “Temporary Viewing Platforms” atop one of the empty frames. The exhibition was part of a larger project offering participants an alternative tour of the city’s most unusual and generally inaccessible overlook points.

Other individuals, drawing considerable scorn from neighboring babas (Serbian for “old women”), found the remote space an ideal place to get high. As one baba raged during one tour of the site, “they’re terrible! All of these years have been terrible. Nothing but junkies.” With a disapproving shake of the head she repeated the Serbian word for “junkie”: narkoman.

Soon, the inevitable rumors about the performance of cult-like rituals began to circulate, while local graffiti artists and taggers went to work on the blank walls. Interestingly, the structures were allegedly used for their intended purpose on at least one occasion. Putnik reports one unexpected encounter at the site: as she scouted one structure in preparation for her exhibition, she heard sounds indicating that there were other people inside. Frightened, she approached the group with caution. As she got closer, it appeared that they were distressed and wanted to avoid her. When they finally acknowledged her directly, they explained that they were a group of professional scientists. Putnik states they appeared to be testing materials by dropping them from the structure’s upper levels. The group was worried about being discovered as their experiments were unlicensed and illegal.

Until this year, these stories and cement structures were all that remained of the dream of Silicon Valley Yugoslavia. Today, after more than twenty years of abandonment, the project has been revived and construction has resumed. While the scale of the plan is somewhat more modest than the Yugoslav original, developers expect that the park will have a significant impact on Serbia’s ailing economy. The team projects that the new facilities will generate hundreds of new jobs, attract extensive foreign investment, and just as Dr. Milicevic had hoped in 1989, encourage the repatriation of young Serbian scientists and researchers from abroad.

Until this year, these stories and cement structures were all that remained of the dream of Silicon Valley Yugoslavia. Today, after more than twenty years of abandonment, the project has been revived and construction has resumed. While the scale of the plan is somewhat more modest than the Yugoslav original, developers expect that the park will have a significant impact on Serbia’s ailing economy. The team projects that the new facilities will generate hundreds of new jobs, attract extensive foreign investment, and just as Dr. Milicevic had hoped in 1989, encourage the repatriation of young Serbian scientists and researchers from abroad.

And so the dream that had its origin in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia will be realized in the Republic of Serbia. Visiting the site, it’s hard not to think about the many ambitious building plans and developments –in Serbia and around the world- that have been abandoned mid-completion due to our own era’s economic crisis.

In a recent article entitled “The Ruins of the Future”, Yale professor of architecture Sam Jacobs writes of these projects: “Designed for one scenario, buildings find themselves completed in a different landscape, appearing on the skyline like giant mausolea for a failed ideology, or abandoned half-built like freshly minted ruins.” Watching these once-empty skeletons being fit with panels of reflective glass, one wonders if these other abandoned projects will ever be rediscovered and put to use- perhaps in some future, unknown country- like Silicon Valley Yugoslavia.