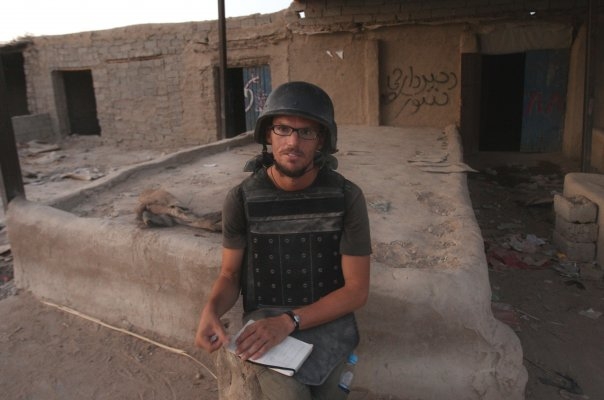

Battlefield reporter, football lover and self-proclaimed media junkie Boštjan Videmšek speaks to Bturn about jogging in war-ridden countries, personality-building traits of three-chord punk music and connections between the Arab Spring and European austerity measures

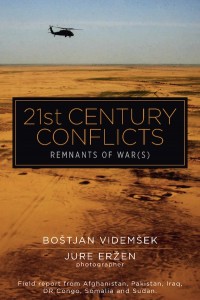

Boštjan Videmšek has been a war correspondent for the better part of the last fourteen years. It was in 1998 war in Kosovo, when he got his first chance to report from the frontline, after which he never turned back. Setting his foot to where most of us would not even dare to travel, he interviewed Taliban leaders, Iraqi and Libyan rebels, Hezbollah and Hamas politicians, Egyptian protesters, Syrian freedom fighters… In August, he authored a book, 21st Century Conflicts: Remnants of War(s), which combines journalistic reports from, and analytical insights on, bloody conflicts in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, DR Congo, Somalia and Sudan. “I became a witness to history,” Videmšek writes in the introduction, “which was both a privilege and a daunting trial.”

Passionately displaying his encyclopedic knowledge of Yugoslav successes in sports, Videmšek despises Yugonostalgia and feels nothing but more or less contempt for Slovenia, his home country. While speaking in Slovenian he regularly uses Serbo-Croatian and English phrases, particularly when getting upset over certain topics. Since I called him on the day the legendary KUD Idijoti punk band frontman died, Videmšek dedicated this interview to him. R.I.P. Tusta.

Returning recently from Syria and moving on to Greece next week, you obviously follow the developments of the Arab Spring, as well as European austerity mania. Is it a relief for you to be back in Slovenia?

It used to be. But it’s completely different these days. It’s a challenge now because all the senses of the Third World, from smell to touch, are almost here. What used to be exotic is becoming domestic. The remainders of the European welfare state are being overtaken on the right by the Third World measures. In two years, we will become Moldova with Danish taxes. That’s for sure. There’s no way out. This is the reason why I’ve been travelling to Greece non-stop, watching a society decaying while still alive. The way infrastructure is being destroyed there can be compared only to war. And, in structural sense, we are rapidly following Greece’s footsteps. We are constantly adopting the same reforms that were imposed on Greece by the troika: Brussels, Berlin, international financial institutions. It’s happening here, too, yet much faster. What Greece has adopted in two years, Slovenia will adopt in four or five months. It’s similar in Spain of course, which is becoming my home away from home, too.

In these times of hyper decomposition of Slovenia and Europe as we know them, I feel it is professionally irresponsible and personally unethical not to cover European issues and not to invest oneself in an area, which is facing organic decomposition. To focus my work on non-domestic issues right now would be escaping responsibility. So, I write comparative stories and portraits of rebels from various cities in Europe and Arab world with an emphasis on resistance. The European Fall versus the Arab Spring. About how we are handling the loss of what we had – we are sore losers and offer no alternative. And about how those, who had nothing, fought the totalitarian regimes, which resulted in producing far more positive energy than over here. Ethics of losing meets ethics of gaining. This is the area where a proper journalist has much to observe, say and judge.

So, you sense the seeds of what an alternative might be in the Arab world, yet not in Europe. What exactly is this alternative you sense?

In reality, in Europe, we’ve spent our credits. Our loans are so huge that we’ve been left without credit. In the first weeks of the Egyptian revolution, every person at Tahrir Square whom I came across was a political being. Everyone! I’m speaking of the revolutionary core of course, the protesters, not the silent majority that had done nothing throughout and got manipulated further when the revolution was finally stolen. Each of these persons had a political agenda with clear and articulate message and without ballast. “We want a particular type of society which has nothing to do with Europe. We saw what happened in Eastern Europe after the fall of Berlin wall.” Capitalism entered the “empty space” of one ideology, took everything that was left intact, and turned it into ashes. Two immense social-political-economic concepts hence destroyed a huge space and took away from us even the possibility of decision-making. That’s where we’re at today.

Young, educated Arabs realised the West hasn’t been a promised land for some time now. In addition, they saw what an extreme version of Islamised society looks like. Hence they didn’t have a lot of wet dreams anymore. Sticking to no illusions, they started creating a new version of political Islam, in which, on the one hand, the secular minority, which was in the forefront of the revolution, gained almost nothing, but on the other hand, the extreme forces, which might have usurped the momentum, remained tamed. Except in Syria where this has actually been escalating into a civil war between Sunni and Shia, yet mainly due to external reasons having to do with Russian, Chinese, American, Saudi, Qatari and Turkish political and economic interests.

When revolution was happening at Tahrir Square, I wrote: “It’s time for us to stop exporting democracy and start importing it.” It was beautiful. Never before, no matter where I’ve been, have I felt such hope that something can be changed. A sort of teenage idealism settled in my old bones. Not for long though. In a few months, it was clear – the revolution had been stolen by the army and, after the elections, by the Muslim Brotherhood.

Isn’t that a key paradox here? You connect the true alternative with secular Arab movements, who oppose Islamisation and don’t accept colonisation from brutal capitalist forces. Yet their revolution got stolen and now they basically can’t influence the way their societies are being organised and governed.

They had very little time. This highly secular, very educated group of people – who would basically be our friends here – is seriously small. Nevertheless, this is the group that led crowds onto the streets and sent messages over social networks to their compatriots and to the world. This is the group that 100.000 people, at a certain point even 1.5 million people, followed onto the streets. They moved from behind electronic screens onto analog squares. But in Egypt of 85 million residents that was almost nothing. It was strong and efficient enough however to overthrow the regime. Mubarak was sentenced to life imprisonment, which two years ago would have seemed like a science fiction story.

They had very little time. This highly secular, very educated group of people – who would basically be our friends here – is seriously small. Nevertheless, this is the group that led crowds onto the streets and sent messages over social networks to their compatriots and to the world. This is the group that 100.000 people, at a certain point even 1.5 million people, followed onto the streets. They moved from behind electronic screens onto analog squares. But in Egypt of 85 million residents that was almost nothing. It was strong and efficient enough however to overthrow the regime. Mubarak was sentenced to life imprisonment, which two years ago would have seemed like a science fiction story.

This of course didn’t affect the “silent regime” of intelligence, secret police and army. So by the time national elections were to take place, it became clear that the seculars haven’t got a chance. As much as the society lacked the democratic basis they lacked the historical tradition.

People hence turned to Muslim Brotherhood whose election campaign lasted for the last eighty years, taking care of the municipal services not provided by the state: they cleaned the streets and toilets, baked bread, their doctors cured patients for free etc. They made people’s lives in local communities bearable and this finally resulted in them taking over the country. Muslim Brotherhood came from landfill to power. They became so strong that even the army had to pay its respect and back off. Since in power, they nevertheless have behaved extremely wise in political sense. They don’t allow the brutal Islamisation to thrive and regularly talk to the youth.

How about other Arab countries after the revolution?

Syria is the bloodiest conflict of 21st century so far. And it’s only going to get worse. In Libya, the secular parties won the election, but the country is still unsafe, edgy and on the brink of collapse. In Tunisia, there’s a very gentle political Islam. Yemen is governed by Saudi-American forces and serves as a training ground to fight Al-Qaeda. The rest is geo-politically irrelevant.

Since I know you love playing football, I guess you’ve been kicking the ball in dangerous areas as well, right? Any interesting stories in this regard?

I regularly play football with the locals. It’s always a very beautiful experience. Two, however, were rather extreme. The first one was in Jebel Mara, Darfur, where me and a Spanish reporter, David Beriain, were the first to reach the rebels in 2004. Near the frontline there was a space where all the children of combatants were gathered. Not a refugee camp, more like a gigantic open air safe house. But there were no women around either as they were taking care of the fields. There was approximately 400 children there. And one football. When we arrived a kid passed us the ball, me and David played with it for a while, and before you know it the two of us and 400 children were running after the ball across those plains for two whole hours, freaking out, shouting. Pure happiness in total darkness. Amazing.

The second extreme experience took place in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, right after the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami. The place was torn to the ground. There was a twelve year old boy there. He and his dad were the only ones in the family who had survived. Me and the boy were passing the ball between each other. Hitting my t-shirt, the ball left a muddy mark each time. These marks seemed like remains of the bodies. 180.000 people died there; their bodies mixed into the flattened ground. One of the most horrific things I’ve experienced. All of a sudden, the kid stopped playing and ran to a spot not far away. Checking the muddy ground, he found a head. Just a head. “I found my mother’s head,” he shouted, “would you like to see it?” At that point, one can only shiver. One can’t react at all. It’s not in our DNA to. In six or seven minutes however we started passing the ball between each other again, as if nothing had happened. Smiles on our faces. Relaxed.

What’s the moral of this story, of this fable almost? In natural disasters everybody is innocent. Although terrible, natural disasters are in a sense beautiful to cover because they bring out the best in people. They don’t produce revenge, rage, nothingness. In such situation, one can only go from nothingness upwards. And this child started anew. It was a catharsis. And football helped. Football is the only universal language.

What kind of music do you normally listen to?

Same as in ’94. My musical progress stopped when I finished high school. So, lots of punk rock, though my favourite band will forever be The Pixies. Well, it’s true that I softened a little bit at college, listening to the likes of Smashing Pumpkins, but I grew up on MDC, Dead Kennedys, Bad Religion, Ramones and Yugoslav new wave naturally. That’s the way it still is. Mostly the three-chord stuff.

Since your lifestyle is so different than those of most people in our generation, I’m wondering about your attitude towards people like me, who regularly follow new music releases, movie production, popular culture in general. Do you feel these are distractions in life in terms of keeping people occupied with nonsense while forgetting about huge inequalities that govern our societies?

One couldn’t be more preoccupied with popular culture than I am. I grew up on this, too, you know. As did all my friends. It was our common language. It still is. Also, a particular personal ethics was formed through consumption of popular culture. My sense of equality and justice most certainly developed also through music lyrics. It was hence the opposite – popular culture didn’t distract my attention from issues of right and wrong, it encouraged it. This is the reason I said my musical progress stopped in 1994. Since that time – not that I was searching very eagerly, though – I haven’t really found a band that would explain the world in my language, according to my personal and professional ethics. Yet I still listen to Minor Threat, MDC and even early Bad Religion, who tell me the same things, with the same intensity, as they did when I was in the 2nd year of high school.

It’s true however that I used to be a complete film buff but, in the last three or four years, my engagement with popular culture started shifting in direction of literature. Although a media junkie, I try to reduce media consumption in favour of books. The way I see it, only in literature the wholeness of truth and all the colours of the soul are present. I read enormous quantities of everything. Hence suffers music and, particularly, film. Not so much documentaries, mostly feature films. In short, I am trying to escape from fiction into stuff that is much more reflected. I’m sprinting from reflexes to reflection. I do however envy people, who are obsessively playing games.

Playing computer games?

This is what I’ve been constantly craving. In case something happened to me, I’d already have a plan. If my leg was to get blown away – though I hope that never happens – I can picture myself on opiates with a playstation in my hands. In case like that, playing games seems like a pretty reasonable future. I could make up for the last thirteen years of radical ascetism.

You mentioned opiates. So, how about dope in extreme situations? Do you do drugs or not?

I haven’t in a long time. Apart from smoking weed on 11 November 2009 during Russia v. Slovenia half-time, Russia leading 1:0. We lost 2:1 in the end. We won nevertheless four days later in Maribor in a return match and qualified for the World Cup in South Africa.

Quiz time! Who played in the ’80 World Cup Yugoslav football team?

In 1980 nobody since there was no World Cup. (laughs) So, either ’78 or ’82?

So much for my memory. So tell me about Mexico ’82 team?

Mexico was in 1986. And Yugoslavia didn’t qualify. (laughs) The Yugoslav team in 1982 however was comprised of the likes of Zlatko Vujović, Ivica Šurjak, Dragan Pantelić, Safet Sušić. You recall this generation, right? Spain. The fat-face boy with a football under his arm. This was the first World Cup I remember following for real, being aware of it.

Do you also contemplate – as many people do – on what would have become of Yugoslav sports if the dissolution of Yugoslavia hadn’t happened?

Well, in the ’92 Summer Olympics, instead of Croatia, Yugoslav basketball team would have played against the Dream Team. A majority of the former Yugoslav team players played for Croatia that summer, and in 27th minute, i. e. in the third minute of the second half, Franjo Arapović scored and put Croatia in a one-point lead. Against the Americans! Who had Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Michael Jordan, Patrick Ewing and Karl Malone on court. And at that point Croatia, a barely internationally recognized country, was in the lead against the Dream Team, which we all looked at like this (leans his head backwards and stares into the ceiling). Imagine what would have happened if that had been a Yugoslav team.

When in the lead, the Croatian coach Mirko Novosel took a timeout and Dražen Petrović came storming in and – this is legendary – started shouting into the microphone: “We’re gonna win!” Next spring, he died in a car accident. Only a day after Croatia lost against Slovenia in a qualifying match in Poland. So, the last game Dražen Petrović ever played was against Slovenia. A year after, another Petrović, who had been a role model of our generation, died. Alpine skier, Rok. These were two really huge losses. They were both extraordinary individuals. Rok Petrović was a hundred years ahead of his time and his death at the bottom of the sea – he was found in a diving suit – is still shrouded in mystery.

When travelling the world, do you say you come from Slovenia or former Yugoslavia? I suppose to most people Yugoslavia is still a more recognisable reference than Slovenia?

A Slovenian passport is an extraordinary thing because nobody asks you anything. They don’t know where to place you. First of all, using this passport, I can go any place. Second, a person, who represents power on the boarder, is faced with a dilemma whether or not he or she will end up looking like a jerk for not knowing where I’m coming from. This has often been the case, for instance, with patriarchal Arabs.

A Slovenian passport is an extraordinary thing because nobody asks you anything. They don’t know where to place you. First of all, using this passport, I can go any place. Second, a person, who represents power on the boarder, is faced with a dilemma whether or not he or she will end up looking like a jerk for not knowing where I’m coming from. This has often been the case, for instance, with patriarchal Arabs.

Nevertheless, I often have to explain that Slovenia used to be a part of Yugoslavia, which is usually followed by the same old, boring story: Tito etc. And I hate that. I’m not a Yugonostalgic! No way. I’m the opposite. I believe Yugonostalgia embodies an erasure of historical memory, it’s an escape from responsibility. 150.000 people attended the fucking Bijelo Dugme reunion concerts! Did you guys forget the war happened or what!? This really pisses me off. Mine is not an emotional relationship with Yugoslavism. It’s a relationship with the kind of Yugoslavism that, living in a false illusion, killed 250.000 people during the 90s Balkan wars. At the same time however I don’t feel anything but more or less contempt for the country I live in today.

At the beginning of your journalistic career you already dealt with subjects that could have put you in physical danger. You reported on street gangs and organised crime, for instance. Is there something within your personality that pushes you towards situations which regular people don’t find particularly safe?

It’s very simple. In the late 80s, when fourteen, I was a member of Green Dragons (Olimpija Ljubljana supporters). That was the time when fan-clashes on football stadiums across Yugoslavia were quite common. I wasn’t fighting though, I just learned where to position myself. I gained not really courage but rather a kind of audacity and resourcefulness. I know how to behave when in a mass of people, I’m aware what’s going on behind my back etc. I still get turned on by violent protests. It’s awesome when the street turns violent, be it Genoa, Belgrade, Cairo, Athens or Madrid. But it all comes from my youth addiction to football matches. So, when at demonstrations, I often start dancing around chanting: “Oh-oh-oh …” (smiles).

But you’ve never been a Slovenian nationalist as loads of football fans have?

Naturally I was a Slovenian nationalist!

You were?

Yes. In the Spring of ’91. However, I wasn’t nationalistic in the sense of tagging others in a negative way. Not at all. I was a sport nationalist. Rooting for our team. Not spreading hatred towards the others. I was fifteen, you know.

Speaking of the late 80s Yugoslavia, have you ever considered a possibility that a huge burden of responsibility for wars in Yugoslavia has been lying on shoulders of the republics which forced the secession agenda at the time, particularly Slovenia?

This is what I’ve been saying, and writing about, all the time (becomes rather upset). Hell, that’s the key, man! We’re co-responsible for Srebrenica genocide. Period. We’re guilty for Dubrovnik, Sarajevo, Vukovar. We’re guilty for Stenkovac refugee camps in the spring of ’99. We’re fucking guilty! Look, I’ve got goose bumps.

I couldn’t understand, although I was merely sixteen at the time, how all of a sudden Karlovac, Croatia – where war was boiling 10 kilometres away from Slovenian border – became perceived by media, politicians and majority of Slovenians as exotica, as if being 1.500 kilometres away. Our peers were dying in thousands in the Balkans – a short ride away – and nobody cared. In 1991, Slovenia let Yugoslav Army leave for Croatia and Bosnia, while Slovenian leadership got intensely involved with arms trade and turned the blind eye to its consequences. Hence we were, no doubt, highly active co-authors of Balkan wars. This is one of the key reasons I started doing what I’ve been doing. Everywhere I go, I see Srebrenica. I’m returning back to Srebrenica as many times as possible for anniversary funeral ceremonies. And feel terribly guilty – each time! Srebrenica is a collateral damage of Slovenian independence.

I’m not aware of a lot of people from Slovenia who would publically support this view?

I’ve been writing about this a lot. In February, after an incident at a handball match between Slovenian Maribor and Bosnian Gradačac, where Maribor supporters shouted the slogan “Knife-Wire-Srebrenica” for couple of minutes, I published a piece pleading for a denial of genocide in Srebrenica to become a criminal offense in Slovenia. Yet nobody responded; there was no reaction.

In Slovenia, historical memory is a nonexistent category. All that matters are Belgrade rafts. Belgrade party rafts and Sarajevo’s Baščaršija affect Slovenian visitors in the same way. Lacking historical memory, they perceive both as complete exotica. “Since you are Balkan southerners, we can reign over you!” This is why there’s over 20.000 students from Slovenia celebrating New Year’s Eve in Belgrade each year. It’s the damn cunts’ sole chance to feel superior. They party because they feel superior, not because they like the vibe at the venue. This is basically rape. It’s disgusting. And herein lies – Israeli leftist could probably explain this very well – a certain hidden collective trauma. Nothing is more disgusting than these Slovenian tourist-bus gangs. And there’s no excuse if you’re sixteen either. What the fuck?! There’s a billion clear messages out there. If you don’t see them, that’s no alibi – you’re an idiot! Piss off! Unless you’re personally affected. That’s different. That’s trauma and it has to be addressed through expert rather than media attention.

What are your plans for the future?

I have quite a few. Amongst others, I’m about to write a book titled Running in the Extreme Zones. It’s about jogging in Baghdad, Kabul, Mogadishu, Darfur, Peshawar etc. Normally, I go running every day. And conflict areas are no exception. Well, it’s true that sometimes it’s impossible. Like for instance in bomb-ridden Syria this summer.

When the fighting takes place on the ground, one knows where the danger zones are. In case of bombing however one doesn’t have a chance. Going jogging would be asking for it. It would be a complete madness. Yet I often go running in order to face my fear. Apart from practicing it to cure my obsessive compulsive disorder, that is. (laughs) The primary reason to go running however is to get myself in contact with ordinary people. You see, when one goes running, one can also walk. When one goes running, one can also talk. And that’s what I do. This way, I experience those places in a completely different light, beyond the concepts of conflict, politics or security. For me, running is basically a direct, though somewhat bizarre, interaction with local people.