As you attempt to navigate the region by plane, it becomes apparent that real distance between nations is better measured in the time, money, and hassle it takes you to get from one place to the next than in kilometers or miles

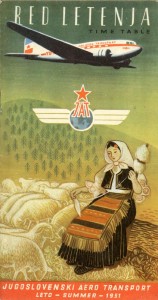

During its heyday, JAT – Yugoslav Airlines had a reputation for excellence and glamour. Its fleet of new Boeing 737s – the first models purchased in Europe and the best-selling jet liners in the history of aviation – transported some five million passengers a year to destinations on five different continents. Its stewardesses won fashion competitions in Paris for the elegance of their uniforms, and the airline’s in-flight meals were considered so superior to those of other carriers that the company took over catering for Air France, among others, in 1967.

Even before the golden era of Yugoslav air travel, the region had a reputation for excellence in aviation. Tiny Pancevo airport, just outside of Belgrade, inaugurated the first night flight in the history of air travel all the way back in 1923. The flight flew to Bucharest and was launched because it was believed that the only way to beat the Orient Express was to fly by night.

But some twenty years after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the carrier, which is now the official airline of Serbia, flies roughly one fifth of the passengers it once did. Though JAT still boasts one of the best safety records of any airline in the world, its fleet of 737s – once a trademark of JAT’s modernity, is aging rapidly. One recent passenger from Britain felt compelled to note online, “the airplane’s cabin smelled strongly of stale smoke”, and remarked that JAT was the only plane they’d seen in recent memory in which an ashtray was installed in the arm rest. Indeed, a few years ago, footage emerged on YouTube of a JAT captain smoking in the cockpit as he piloted a Boeing 727 (which is equipped to transport between 149 and 189 passengers) on its descent into Belgrade’s Nikola Tesla airport.

[JAT captain smoking a fag in cabin. Visible around 3:30]

If JAT’s safety standards and prestige have suffered in recent years, so has the quality of its management: during the last decade, JAT has had six different CEOs, all political appointees and most completely unfamiliar with the airline industry. One was a lawyer, another an airport ground handler, and another a worker at a Centrotekstil shop in Moscow. In his guise as JAT CEO, the former shop worker famously told the media, “I never fly with JAT so I can leave seats open for potential passengers.” Another CEO decided the best way to improve business was to make airline tickets available for sale in post offices. Meanwhile, one recent CEO mismanaged the company so badly that employees in the catering department went on strike, leaving the airline unable to offer anything but water aboard flights for three months. And then there was the JAT CEO and Milosevic crony who was shot dead one night while walking his dog.

But perhaps the most inescapable sign of the decline in the quality of air travel in the region is the complete inability to efficiently get around in an airplane in the first place. Though this summer marks the reopening of flights between coastal Croatia and Serbia after a 21-year suspension following the war, there are still no flights operating between Zagreb and Belgrade, the capitals of the respective countries.

More absurd is that what is impossible today was routine decades ago, not only during the Yugoslav era, but in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Aeroput, the precursor to JAT, began flying airplanes between the Zagreb and Belgrade in 1928. Nowadays, a flight between the capitals will probably require a stopover in a city that way overshoots your intended destination. A recent search for a flight from Zagreb to Belgrade informed me that I’d have to stopover at Ataturk airport in Istanbul before I could get to Serbia, meaning I’d be traveling for more than eight hours – quite a long haul considering the distance between the two cities is 365 kilometers. And the price for this less-than-favorable itinerary? Close to 400 Euros. Not exactly a score given the fact that I flew round trip from Budapest to San Francisco for less than a hundred dollars more this winter.

Attempting to travel between Tirana, Albania and Belgrade is equally inconvenient. Though the countries are in the same neighborhood geographically, “getting there”, as Lonely Planet would call it, is obscenely difficult. Unless you want to fly backwards into the EU, the trip will likely require more than one mode of transportation, an awkward circumnavigation route to avoid passport control at the disputed Kosovo/Serbia border, and many, many hours of your precious time. Again, this arduous journey could easily be completed with a direct flight as far back as 1946. As one attempts to navigate the region by plane, it quickly becomes apparent that real “distance” between nations is better measured in the time, money, and hassle it takes you to get from one place to the next than in kilometers or miles. Degrees of reconciliation are evident in the number of stopovers required to reach your final destination. Even more troubling, the lack of decent transportation options can discourage regional travel and contact between people of different nationalities.

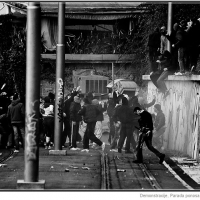

Which is why when Ulrich Schulte, Secretary General of the Association of European airlines, told a Slovenian newspaper earlier this year that the national airlines in the region needed to form a single “Ex-Yu” carrier or risk folding completely, passions flew. Yugonostalgics and those eager for signs of regional cooperation were ecstatic. Others were quick to shoot the idea down like a two-seater sports plane at a Serbian wedding celebration. As one commenter wrote on a blog devoted to aviation in the former Yugoslavia, “My question to Mr. Schulte would be: If you have one bag of shit and you put it next to another one, isn’t it still big pile of shit?”

Others offered more constructive criticism. Many wondered how the participating countries could ever decide on where to place the airline’s hub, given the region’s history of territorial disputes.

Despite the cynicism, the idea of a regional airline to reunite Yugoslavia, at least in airspace, continues to offer some appeal, as most of the national carriers continue to face severe losses, labor strikes, and the threat of bankruptcy. Consequently, flying JAT, like many other airlines in the world hit by the economic crisis, is not what it used to be.