Each of the fifty-two stuffed toy donkeys in Sanja Ivekovic’s installation at dOCUMENTA 13 is labeled with names of historical political figures, from Rosa Luxembourg and Martin Luther King to Che Guevara and Ahmed Basiony of the Arab Spring. Halfway between tragedy and irony, Ivekovic raises a few questions about the role of political resistance in our turbulent global world today

My friend introduced me to most people as a virgin, a documenta virgin. dOCUMENTA (13) is the first Documenta that I have visited. As an attendant of a few previous Venice Biennales and some art fairs, I had certain preconceptions about what I might see. Having fallen in love with the book The Next Documenta Should Be Curated by an Artist, which wittingly exposed the contemporary issue of the ominous exchange of roles between the artist and the curator, I was curious about the extent to which the curator’s role and process would be visible in the exhibition itself.

The first impression I had upon arriving in Kassel was that it was a somewhat typical German city that had been badly damaged by the war and was unfortunately rebuilt in the socialist period rather than extravagantly piled up with shopping malls during the past couple of decades. It does however have a rather fascinating glow of the unusual, because since 1955, every five years, for 100 days, it has become the pedestal of the art world.

Since 1972, the curator or director has also been selected, making it one of the most prestigious roles a curator can hold. The importance of the curator is visible, made visible, equal to that of a director of a large art institution, except slightly more about the diminishing of the boundary between the curator and the artist.

Documenta does not separate artists according to nationality but rather selects works and artists that are placed together to compliment one another to realize the curator’s concept.

It is an exhibition that guides and allows for guidance, offering ideas but not forcing them on the audience. It creates a space that invites the viewer to think, imagine, create, and recreate. A distinct emphasis has been put on history, historical events and recreation.

The work of Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovic embodies all of these ideas. Ivekovic has been on the art scene, present at biennials and large expositions for many decades. Yet her name has not reached the popular masses, perhaps due to the nature of her work itself and also to the her personal views of her own role as an artist.

This year at MOMA in New York Ivekovic presented a small but relevant survey show called Sweet Violence, and in the interviews and articles following the exhibition, she had made her views of the art world and the role of the artist very clear to a broader audience. Her humble view of her genius is that it is the product of the labors of many people, rather than simply her own. It is the exact representation of the artist’s interests in society, and its workings in the present and throughout history.

Studying in ex-Yugoslavia in the mid-1960s, at the time of the student uprisings of 1968, Ivekovic was part of the new Yugoslavian avant garde of conceptualism and performance. A self-proclaimed feminist, Ivekovic’s interests in society, politics, and aesthetics have always intersected.

Her work at a previous Documenta: a field of planted poppy flowers, on the square, Friedrichplatz, the main site of Documenta.

The symbolism of the site itself, which was once used by the National Socialists for military parades and rallies, coupled with the many symbols associated with the poppies that English-speaking nations use to represent the memory of soldiers killed in wars, and that the Eastern bloc countries appropriated as emblems of resistance and revolution (while also recalling their role in the never ending struggle of drug trafficking and abuse), made the piece a truly remarkable reference for the exhibition, and had the considerable visual effect of supreme aestheticization.

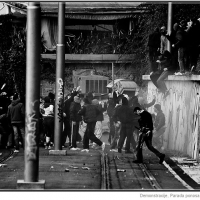

Sanja Ivekovic: The Disobedient (The Revolutionaries) 2012 / photo: Anders Sune Berg, courtesy of dOCUMENTA (13)

This year the artist has again remained true to her views of engaging sociopolitical struggle and the visual arts. Upon entering the space, in the Neue Gallerie, on the first floor, one notices a glaring whiteness, a minimal composition. The work is entitled The Disobedient. One wall is covered with A4 printed texts, and a black &white image is placed in a frame beside the texts. It is a photograph from the newspaper Hessische Volkswacht from April 1933. It depicts a Nazi soldier and a donkey in an enclosed, barbed wire area, surrounded by an observing audience. In the caption below the photograph we can read that the performance was an exercise to warn people about buying from Jewish-owned stores, it was meant as a make believe ‘concentration camp for stubborn citizens’.

As a reaction to this image, the artist’s installation on the adjacent wall, opposite the A4 printed texts, is a large cabinet, recalling pharmaceutical furniture, or a cabinet for taxidermy. The cabinet instead contains 52 stuffed toy donkeys. These donkeys are from different collections and different periods, dating back as far as WWI. Each donkey has a label; on each is a name of an individual that resisted and objected to the injustice and oppression in a given society, with examples as recent as Ahmed Basiony’s death in the Arab Spring in 2011, to historical examples such as Rosa Luxemburg’s death fighting political oppression in 1919. The texts opposite the cabinet are short biographies of these individuals and a brief description of their struggle, just long enough for an emotional pause.

The toys slouching in the glass cabinet with names like Dr. Martin Luther King, Primo Levi, Che Guevara, seem slightly comical on their own, but tragic at the same time. It is a work that speaks of the cruelty of the history of mankind and the bravura of these individuals that sacrificed their lives for a cause much greater than simple existence. Ironically compared to the donkey, an animal often misinterpreted in depictions as representing the dumb working class laborer, but an animal also referred to as the beast of burden.