Could things have been different for Hungary today if it had a revolution back in 1989?

Fluffy patches of clouds drift over a windy hilltop at the outskirts of Budapest. There is little urban settlement out here and the scenery is dominated by a red brick gate with bronze casts of Marx and Lenin greeting the curious visitor. Opposite the entrance is a 12-foot tall grandstand carrying a pair of oversized iron boots that once belonged to a colossal statue of Joseph Stalin. This is Budapest’s Memento Park, built in 1993, shortly after the fall of communism, commemorating the visual iconography of four decades under communist rule in the Hungarian capital.

“Sure you want to go?” a local asks. “There’s nothing out there. And it’s too far away from the city.”

Inside Memento’s walled gates there is a strange, boring silence. The statues are scattered in a seemingly disordered fashion, neither chronologically nor stylistically, some looking menacing, some grandiose, others unremarkable. The park appears dilapidated, as if built in the era it is trying to convey only to have gradually fallen into decay over the years.

A group of Finnish students roams the surroundings. “We came here to learn more about communism”, one boy says. Another explains laconically: “Communism was bad. It didn’t work”. They don’t seem too impressed by the installation. Without detailed plaques or explanations the statues don’t say much, unless youáve pay the private guided tour.

When I mention the uncanny Finnish-Soviet relationship after the WWII, one student is swift to reply:

“We were never conquered by the Russians.”

Indeed, neither was Hungary, but following the downfall of the short-lived local Nazi government in WWII, the country spent forty years under communism, much of it marked in public consciousness by the 1950s Stalinist repression. For a brief moment in 1956, when the colossal 25-meter tall statue of the Soviet leader in Budapest was sawn down from the boots up, it seemed the regime had been toppled along with it. And yet in the decades following the brutal Soviet reprisal, from the 1960s onwards, the country continued with a moderate and long lasting version of communist rule, making Hungary ironically, the “happiest barrack of the Eastern Bloc”.

The idea to remove the statues from the city and place them in a suburban theme park seemed to some to be the perfect solution for the country’s post-1989 debate on what should be done with the most prominent communist symbols. Some wanted them to remain, others asked they be removed or even destroyed. The cleansing of communist iconography from public spaces turned into a widespread practice amongst post-communist societies in the process of re-writing histories: from changing street names, to removing monuments of Soviet heroes and local communist elites.

However, whereas the iconoclastic images of toppling down leaders’ statues – from Lenin and Stalin to Saddam and Gaddafi – have become a template for all dictatorship downfalls, Hungary had experienced a non-violent, almost silent transformation in 1989. With no guns fired and very few acts of vandalizing the communist symbols, the regime quietly dismantled itself.

“I believe dark spots in history stay with you, they live with you subconsciously” says Tamás Álmos, a 26-year old sociology graduate. “Hungarian society never had to confront its unresolved issues from the past. We have never faced our participation in the Holocaust. It was erased. And again, after 1989, we never looked back and reflected on our communist era. This kind of passivity and let-go attitude has remained even with younger generations. Of course, this leaves room for far right movements and their quick and simple answers to complex issues to capture youth minds.”

Inside the House of Terror

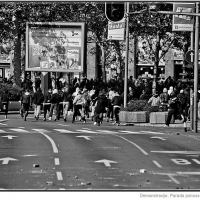

Could things have been different for Hungary today if it had a revolution back in 1989? I am heading down Andrássy út, a grand 4-track boulevard and one of the main pulsating city arteries, once the location of the notorious prison and interrogation centre, first of the Nazis, then of the Communists. Today, the street boasts an array of Audis and BMWs flashing past Louis Vuittons and D&G’s shopping windows, but Andrássy út No 60 was once known and feared by every Budapest citizen. The address evokes painful memories of all those who had been detained, interrogated, tortured or killed inside. Ten years ago, the building was transformed into an impressive, yet somewhat controversial House of Terror.

In sharp contrast to the frozen letargia of the Memento park, inside the Terror Háza it is bursting with life. Even more so, for much around here is nothing but death and torture. Designed by the renowned architect and Hollywood set-designer Attila Kovacs, the museum is a spectacular display of the captivating powers of totalitarian iconography.

“The idea was to understand history without verbal expression”, Kovacs tells me. “Like in a silent movie, using art installation as language”.

Captured in carefully arranged exhibits such as military and police uniforms, office furniture, spying equipment, murals, walls, posters, and books, accompanied by multiple video screens and occasionally pumping industrial music, the museum recreates almost every object imaginable in the daily life of terror. Deep down in the basement, prison cells remind us how the victims must have felt. As if coming out of a David Lynch film or a Laibach stage performance, Kovacs’ installation is all about the dark side.

From an artistic perspective, House of Terror is a provocative masterpiece, but from a political standpoint, the public institution founded by the government in 2002 during current Hungarian PM Viktor Orban’s first mandate, is shrouded with doubt.

Orban, who returned to power in 2010, after two mandates of socialist government, is well known as EU leaders’ ‘rude boy’, thanks to his recent sweeping adoption of legislation that seemed to undermine the Union’s basic principles of democracy. The liberal who once gave the historic speech in one of the key public events in recent Hungarian history – reburial of the executed dissident Hungarian PM Imre Nagy in 1989 – reinvented himself as a right wing conservative, and naturally, a vigorous anti-communist. However, many argue that Orban’s strong anti-communist rhetoric is just another tool for strengthening his grip on power and disqualifying his socialist opponents from the local political arena.

Critics say the museum is the only one in the world that equates the crimes of Nazism and Stalinism. A decade after its opening, the House of Terror remains a delicate subject. In many ways, the battle for political memory in Hungary has become the battleground for influence on current political debates.

Symbols talk, don’t they?

I step out of the museum, impressed with Kovac’s masterful art direction but filled with a sense of dread and nausea. On the way back to my hotel, I take a detour. It’s time to pay a visit to an unlikely leftover from the communist time.

Situated at Freedom Square (Szabadság tér), the memorial to the The Red Army soldiers who lost their lives capturing the city from the Nazis in 1945 is now surrounded by a protective metal fence. Behind it, a row of trees completely obscures the monument’s lower base, but far from a socialist-realist kitsch, the marble obelisk still climbs tall and proud, alas bland and unexceptional.

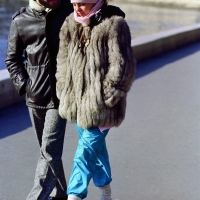

Opposite of it, I see a familiar figure surrounded by a group of tourists. He is standing freely, almost jovially looking. Palms stretched, his feet on the ground, making a step towards the Soviet memorial.

“This is a statue of Ronald Reagan, former President of the United States, set up nine months ago”, a local guide explains to a group of tourists. “Reagan helped end communism and the Hungarian people wanted to honour him for his deeds.”

A grin pops up on the President’s face, as if he’s eavesdropping. If he could walk now, he would run to the obelisk, point a finger and shout: “Gotcha!”

I give Ronnie a hi-five and hit back to catch my tram. I remember how Robert Musil once said monuments are “invisible”. We past next to them everyday, but we are more influenced by flashing of advertising billboards than dead pieces of marble and metal. But perhaps Musil was wrong. The very silence of political symbols keeps them persistently inscribed in our everyday lives. Even more so if the symbols hang ‘unnoticed’ in public space, they do ‘talk’ to us.

Only a few feet away, I bump into another familiar face. I saw him just a few hours ago in a footage inside the House of Terror, calmly confronting the Stalinist persecutors before his death. Now cast in bronze, he leans onto a little metal bridge, facing his back to Reagan and the Red Army. Obviously understated, as if to differ as much as possible from the megalomania of Stalinist imagery, the former Prime Minister Imre Nagy seems relaxed, deep in his thoughts, gazing towards the Hungarian Parliament on the bank of the Danube. I give him a quick salute and as the sun slowly sets, I rush towards the tram station. All I can think now is how this strange, buzzing Hungarian debate with political ghosts, iron statues and marble pedestals is far from over.