One of the most exciting documentary filmmakers today speaks about his creative process when dealing with delicate human issues in a world one rarely has access to

The city of Belgrade has recently hosted the film director and cinematographer Michael Glawogger, whose triptych Whore’s Glory closed the The Magnificent 7 documentary film festival, held in an impressive postmodernist-style congress hall „Sava center“ with the largest big screen in Europe (yes, it’s bigger than the one in Palais de Cannes). Among many festival guests, Glawogger was certainly „the star“ and his film left the audience utterly impressed.

Whore’s Glory is the last movie in his trilogy about the globalization of the proletariat, which also includes Megacities (1998) and Workingman’s Death (2005). It deals with prostitution inside three culturally different environments (Thailand, Bangladesh, Mexico), stepping deeper into the world’s oldest profession than any film before. The degree of Glawogger’s access to sex workers and their clients, along with their willingness to not only speak, but also live their lives (ultimately smoking crack and performing sex) in front of the camera is impressive.

In Belgrade, Michael spent a few hours explaining the process of making this film which took almost 4 years of his life. We asked him what are the special powers one should have in order to come as close to the subject as it is necessary to portrait it so precisely?

“There is no special power, it’s the time and you gotta want it. Not anybody could do it cause it takes so much of your life. If you don’t invest the time and if you don’t like the people and if you don’t want to do that – you never can. Because, they will realize it. It’s very, very time consuming. Also, the more movies you do the more people stick to you. If you’re the kind of person who likes to stay in your own world, always with the same people or live in the house in the suburbs that’s not the kind of a life you can lead. This is not a job, it’s a life.

If you want to get people to talk to you – you have to come back many times. For prostitutes it is unusual if you come back, they see you either as a potential regular customer or they realize you are really interested in them. It sounds really funky when you say – 3 years of my life I travelled around to see brothels. Everyone says – hey, cool job! But it’s not like that in a way because you really enter this world and become friends with these people. In this movie, the practical side was a bit more challenging because I got along with the women very well and I became really interested in them, they have experienced so many things I will never come to experience.”

In the process of making this remarkable documentary, Glawogger had the least problems in negotiating with mafia and pimps.

“Mafia was the most reliable partner in this project. We would talk to the guys, present them our idea, they would think about it for a while, negotiate the price. We would pay them and got an approval to shoot the girls. The most interesting thing is that they don’t control the girls completely. They tell you you can shoot, but in the end it’s the girls who decide if they want to be filmed or not. The biggest challenge laid to even get access and their resistance in any kind of representation. But, at the moment they open up they were very giving.”

While explaining his human and delicate approach to girls portrayed in his film, Glawogger spontaneously touched the superficial journalistic style of dealing with the same subject. We could get the idea he’s not very fond of it:

“I give you an example – you have a fishtank in Cambodia and some CNN reporter rushes in with his camera and sees all the girls running away. And in the commentary he assumed that they are running away because they are afraid of something at their work. The truth is you just don’t do that, you don’t run in with a camera and disturb other people’s doings and privacy. So, they assume because it’s prostitution and it’s morally bad that they can do anything. People go to brothels , film with a hidden camera and say they are all victims. The girls go crazy over that. They say – we are not victims. Nobody told them, nobody asked them to film. So, with this kind of journalism I don’t want to be even compared. I don’t want to say that there is not a lot of very good journalists who do a very ethical job. It’s very different from mine, but in that sense I oppose.”

Whores’ Glory has the discipline of a clear-eyed, observational documentary. With an engaging cinematic style many faces of prostitution are observed closely and with nonjudgmental detachment. Never exploitative, this film has nothing new to say about prostitution, but it does change one’s perspective totally. Glawogger explains why there’s no such thing as an “objective film making”?

“It would be horrible if it would be objective! There is no such thing, it’s just a huge big lie. If anyone says it exists it would bore the shit out of everybody. Filmmaking is like an art. You have a stand-point and the view of the world and you show it. Everything else is nothing. So, what’s the talk about being objective? It doesn’t exist. You can’t depict reality without interference, without making a craft of it, without showing it through your eyes. It just doesn’t exist. It’s a myth.

My idea is to present things differently with the way of looking that you normally don’t look at that. Otherwise – what’s the big news if I say that prostitution is bad or good. It amounts to nothing. It will always be there. Obviously there is a strong desire for human beings to do that. And if it’s not a desire then maybe a need. There is something in the soul of a man that obviously wants to buy that and there’s some need in the easiness or in the apparent easiness of selling and no law in the world can forbid it. There is no need for me to put a movie on the screen that says the common place like this is good or this is bad. It is! And why it is and how is the everyday life of it is for me so much more interesting than the question if it’s good or bad.”

In the first part of the film, set in and around the Fish Tank brothel in Bangkok, the women stop by a Buddhist shrine to pray before punching a clock, going through hair and make-up as if they were to hit the runaway, finally sitting in a bright glass box from which they are being picked by clients. Prostitution in Thailand is perceived as just another consumer service. The second location is the “City of Joy” red-light district of Faridpur where sex workers and clients believe that if the girls didn’t perform this disgraceful work, men would take to raping women on the streets. One girl explains she won’t perform oral sex because that’s the same mouth she uses to pray to Allah. Still, religion doesn’t get in the way when extremely young girls are sold by their families and Glawogger even recorded a madam haggling over the price for a girl who looks barely past puberty. In Reynosa, Mexico, a town near U.S. border where prostitutes are inhabiting a special area called La Zona, the girls are praying to Lady Death, a quasi-pagan goddess emerged from local interpretation of Catholicism. Questions about the relationship between religion and prostitution seem inevitable.

“It just came up”, says Glawogger. “Because it is obviously so important and it changes so much our sexuality. The whole sexuality in Islamic countries is totally different or in the Buddhist surroundings where there is no such guilt factor as the Catholics have. Catholics put a shit load of guilt on sexualit, maybe that’s why they enjoy it so much.I don’t know, but that’s what happens. The correlation between these two things is quite an important one.”

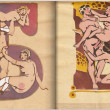

Although disturbingly realistic and harshly true, Whore’s Glory is also extremely stylish. The images flow with rich colours, scenes are structured almost as in a fiction film, still without prettifying. Standout soundtrack with the music by P.J. Harvey, CocoRosie, Antony & The Johnsons and Bjork works as if the picture is there to justify the melancholic feel of a certain song. Unlike many movie-makers today, Glawogger still works with a 16 mm camera.

“It looks a little warmer for me and I don’t really in an artistic way like the over-sharpness of digital imagery. Imagery is your paint, it makes something of a film if you do it this or that way. And also I always enjoyed the restriction of not filming everything or from every angle without even knowing why and how. So, I like to think about it, I like to create an image of my film and the restriction that film has is something valuable is something that works for my process of working. It’s very easy to become irrelevant if you come to the set with camera already turned on and you film everything all the time. It’s really hard to stay relevant these days.”

Changing one’s perception is something of a theme in Glawogger’s work. With Whore’s Glory he might have changed the audience’s perception of prostitution, while in his feature film Slumming (2006) it’s the main character who changes his own perception of life in general. Surprisingly enough, a famous Serbian turbo folk star Dragana Mirkovic has a cameo in this one. Seems like this Austrian is quite into ex-Yugoslavia.

“I love ex-Yugoslavia, cause I was born in Graz which is just 15 km from the border, so we would always go down there. In the beginning of the movie these guys, they play pranks with other people. For example they go to the Turkish restaurant and see the keys at the door and they close the door and throw the key away. Or they go to this bar where Dragana plays and they send the keyboard player roses all the time. Dragana was there just because I liked her and I thought she is great. I was so honoured that she would do it. But she was a little scared at the beginning because she was appearing in the restaurant called ‘Lepa Brena’.

And she said ‘I don’t want to play in a restaurant called Lepa Brena if you can see in the film that it is called like that’. So, we had a big argument about it and finally the sign wasn’t shown and she appeared. I know about Lepa Brena and these people, I like this music. In Vienna this kind of music has a huge following, mostly of Serbs who live in Vienna, but there are a lot of these places. And it was connected to the film because the guys always go to these places where they don’t belong. They deliberately go to the disco club where they have nothing to do. That was the whole idea of their socialization and I was always fascinated by these places. It’s fun to go to these discos and I like the music a lot.