Why are today’s hackers and tech enthusiasts interested in a little build-it-yourself computer from socialist Yugoslavia? The Galaksija’s unexpected success in 1983 sparked a minor computer revolution, and its influence on the region’s personal computer culture is still evident today

“Alternate History” aficionados (who usually spend their time pondering questions like “what would have happened if the Aztecs had resisted Spanish colonization?”) have devoted significant time to speculating about an alternate reality in which the Galaksija exceeded Western models in popularity during the 1980s, saved Yugoslavia from dissolution and made inexpensive microcomputer kits available to the Third World. On the technical side of things, hackers, engineers and artificial intelligence experts continue to write dissertations and emulators in homage to the Galaksija.

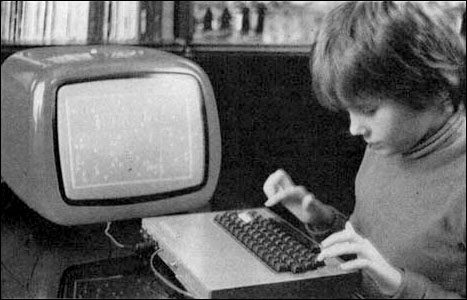

Though the computer used audio tape as its main storage system, had about as much memory as a single e-mail, and produced only three error messages (“WHAT?”, “HOW?” and “SORRY”), back in 1983, every curious tech enthusiast in Yugoslavia wanted a Galaksija to call their own.

“We can only achieve the Computing Revolution if we have a domestic computer,” read an editorial in the country’s first publication devoted to personal computing. Back then, imports on items exceeding a value of 1500 dinars (about 70 Euros today) were forbidden by law. Though some early devotees claim that foreign computers were available on the black market, they were still prohibitively expensive for the average Yugoslav citizen.

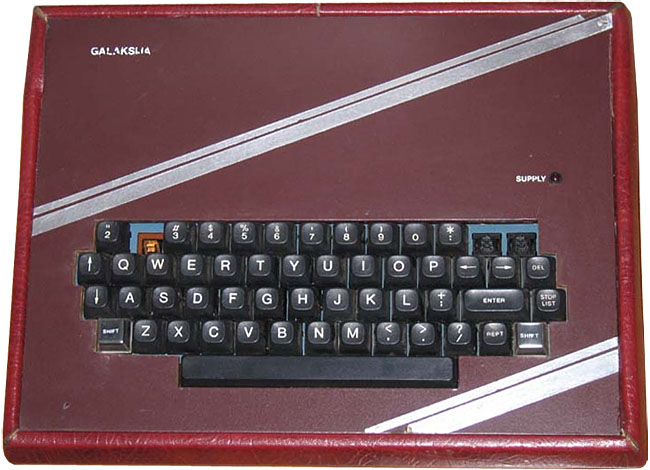

But it was these very restrictions and prohibitions that allowed an exciting domestic computing market to emerge. At the center of this new culture was the Galaksija, a cheap, build-it-yourself microcomputer with a modified BASIC interpreter and fantastically low res graphics.

Many of the region’s talented computer scientists, hackers and designers first fell in love with computers through the Galaksija. The DIY computer kit was the brainchild of Serbian inventor Voja Antonic, who while on holiday in Montenegro had the idea to build an accessible domestic computer that would generate graphics using software on a CPU as opposed to an expensive graphics card.

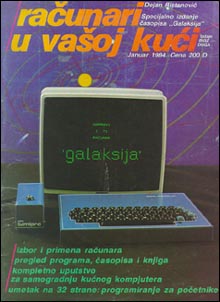

Soon, journalist and tech expert Dejan Ristanovic assembled a special “Computers in Your Home” edition of a popular science magazine called Galaksija, with significant space dedicated to Antonic’s new computer of the same name.

Soon, journalist and tech expert Dejan Ristanovic assembled a special “Computers in Your Home” edition of a popular science magazine called Galaksija, with significant space dedicated to Antonic’s new computer of the same name.

With sales vastly exceeding expectations, the “Computers in Your Home” edition had to be reprinted several times, with a total of 120,000 of the magazines sold.

The little Yugoslav DIY computer was a huge success: in the beginning, Antonic and Ristanovic had hoped that perhaps a few hundred people would order the computer kit. The idea that 1000 people would build a Galaksija was considered so “ridiculously optimistic” that it provoked laughter. But more than 8000 people in Yugoslavia went on to build their very own Galaksija computer.

Many of these users became its programmers and participated in an early version of file sharing. During the mid-1980s, Belgrade radio show Ventilator 202 broadcast computer software live so that listeners could record games and electronic journals onto cassette tapes. Some of this software was programmed and submitted by listeners themselves, reflecting an early open source ethos. Galaksija games like Light Cycle Race and Diamond Mine were available free to anyone with a radio and a tape recorder.

Despite its feeble technology, the Galaksija continues to inspire fascination. Tomaz Solc, an electrical engineer based in Ljubljana, recently wrote his thesis on the Galksija’s technical details (among other discoveries, Solc has concluded that contrary to popular belief, the Galaksija’s operating system was not based on an unauthorized copy of Microsoft BASIC, but on the Tandy TRS-80). Solc has also created a number of Galaksija development tools which he makes available for free on his website.

And Bruno Jakic, an artificial intelligence expert living in the Netherlands, recently wrote a piece about the Galaksija’s place in 1980s New Wave culture. The article, entitled “Computers in Your Home: Galaxy, the New Wave and Computer Culture in Yugoslavia in 1980s”, is currently undergoing review for publication with several international publishers, including MIT. Among many intriguing points, Jakic notes that the Galaksija came without a case, meaning that artists and computer users built and decorated their own. Unlike the mass-produced cases of today, or the Galaksija’s 1980s contemporaries like the clunky Commodore 64 or the beige-colored Macintosh, no two Galaksijas looked alike.

Solc, who spends much of his time at Ljubljana’s Kiberpipa, a hackerspace, cultural center and café, sums up this uniquely Yugoslavian contribution to computer history: “designers of Galaksija, being a couple of years behind state of the art in the West, were actually in a good position to learn from designers of other home computers… it was polished and simplified, but made more versatile at the same time.”