The notorious music culture that became synonymous with Serbia’s former nationalist regime has anything but disappeared. Turbo-folk continues to play the role of both hero and villain – as Serbia’s best known ‘brand’ and a skeleton in its closet.

After several years of investigation, the Serbian authorities have issued an indictment against one of the country’s biggest music stars – Svetlana Raznatovic, who performs under the name “Ceca.” Charged with embezzling funds from a football club in which she was a co-owner and illegal possession of firearms, the singer faced a sentence of up to 15 years in prison, but eventually managed to strike a deal with the prosecution to repay parts of the sum under conditions of house arrest.

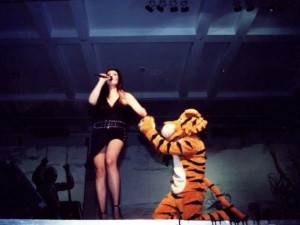

Many see Ceca’s indictment as a symbolic end to the era of “turbo-folk” – the infamous music culture which was the soundtrack of the Serbian 1990s criminal-nationalist establishment. Ceca was the iconic figure of this movement, and her nationally-broadcast wedding to Serbian paramilitary leader Zeljko “Arkan” Raznatovic in 1995 has been cemented as a literal example of the metaphorical marriage between Serbian pop culture and crime during the era of Slobodan Milosevic.

Turbo folk’s notorious reputation as the Serbian cultural menace par excellence was well-earned on multiple levels.

Turbo folk’s notorious reputation as the Serbian cultural menace par excellence was well-earned on multiple levels.

It is viewed as an unattractive hybrid music – a kitsch style created by the collision of Balkan folk and cheap Western dance beats, and then further corrupted by what is seen as an undesirable ‘Oriental’ flair.

Turbo folk’s lyrical emphasis on the easy life of sex, money and fame has also been considered suspect – and held responsible for spreading a sort of ‘moral disease’ throughout Serbian society.

And from the political perspective, it has been argued that the music is a sheer embodiment of Milosevic’s nationalist ideology, as if it were created by the regime itself.

Fast forward a decade after Milosevic’s downfall, however, and turbo-folk still holds a preeminent place on a Serbian cultural map which seems largely unchanged. While urban rock culture had not recovered from its 1990s limbo, turbo-folk has evolved, strengthened and expanded its dominance, suggesting there might be no direct linkage between its cultural force and the ideology of the Milosevic regime. Would Serbian mass culture be unmistakably different today had its ruling elite in the 1990s been democratic, civic and anti-nationalist? Would there be no turbo-folk?

There is reason to think there would still be a turbo-folk. The 1990s ‘turbo’ element that came to dominate the already massively popular folk music in Serbia had more to do with globalization and MTV than with Serbia’s political regime. Songs about quick romance and speedy lifestyle, combined with eroticized imagery can hardly be isolated from wider post-Communist and, indeed, global phenomena. The regime did ostentatiously promote turbo-folk in state-controlled mass media, as a means of both escapism and engagement in nationalistic euphoria, but it remains unclear whether there was anything implicit in the culture itself that would appeal strictly to nationalist or authoritarian sentiments.

In fact, if Milosevic’s regime did manipulate the public through turbo-folk, it was at the same time instrumentalising turbo-folk itself. The fusion of culture and power in Serbia during the 1990s was achieved through the specific media practice of merging politics and entertainment into a seamless whole. Ultimately, it was not the folk superstars who embodied certain politics, it was the nationalist politicians that became superstars in the way folk singers were.

The entertainment talk shows on Serbian television at the time would often consist of one popular actor/actress, one or two folk singers and a politician from the regime. In one of the well known episodes of a prime time show ‘Minimaksovizija’ on TV Politika in 1991, archetypal turbo-folk star Dragana Mirkovic sits bewildered next to Vojislav Seselj – the leader of the then-emerging ultra-nationalist Serbian Radical Party. Much to the amusement of the studio audience, Seselj tells an obscene joke about piercing a Croat man’s skull with a ‘bullet through its forehead’. However, the joke achieves the desirable effect only within the totality and proximity of show’s complete complement of guests. If it were just the politician alone ‘having a bit of a laugh’, the entire stunt would remain an example of warmongering political rhetoric. In the presence of a popular folk singer, however, Seselj’s ultra-extremist discourse is both neutralized and legitimized at the same time, entering the terrain of entertainment: war and politics become part of the estrada.

The entertainment talk shows on Serbian television at the time would often consist of one popular actor/actress, one or two folk singers and a politician from the regime. In one of the well known episodes of a prime time show ‘Minimaksovizija’ on TV Politika in 1991, archetypal turbo-folk star Dragana Mirkovic sits bewildered next to Vojislav Seselj – the leader of the then-emerging ultra-nationalist Serbian Radical Party. Much to the amusement of the studio audience, Seselj tells an obscene joke about piercing a Croat man’s skull with a ‘bullet through its forehead’. However, the joke achieves the desirable effect only within the totality and proximity of show’s complete complement of guests. If it were just the politician alone ‘having a bit of a laugh’, the entire stunt would remain an example of warmongering political rhetoric. In the presence of a popular folk singer, however, Seselj’s ultra-extremist discourse is both neutralized and legitimized at the same time, entering the terrain of entertainment: war and politics become part of the estrada.

Twenty years later, there are none of the armed conflicts or political repression of that specific era. Instead, the Serbian political landscape has been fully circumscribed in the larger mass entertainment world of tabloids and “Big Brother” TV, with Ratko Mladic in the Hague and Serbia on its way to the EU. The iconography of turbo-folk is swiftly spreading across local borders, to neighboring Croatia, yet is not so much a case of switching sides, as much as it is an example of shifting meanings in mass culture.

What critics of turbo-folk fail to acknowledge is that inside this ‘corrupted’ cultural concept there is space for asserting multiple – and often conflicting – ideas and practices. Analyzing the case of an ex-Muslim turbo-folk star Sinan Sakic in his article for Belgrade’s NIN (2006), journalist Zoran Cirjakovic reflects on the ‘Orientalist’ culture discourse of today’s liberal Serbia, emphasizing complex and sometimes controversial roles that turbo-folk artists can maintain in different socio-political environments. Sakic is simultaneously dismissed both by Serbian liberal circles and the Bosnian Islamists – by the former for being too Oriental and Islamist, and by the latter for being too liberal and essentially anti-Islamic. Describing the diversity of Sakic’s audience at a concert at Belgrade’s ‘Tasmajdan’, Cirjakovic finds in turbo-folk the expressions of multi-ethnical and multicultural tolerance – the very same values to which Serbia’s liberal elite aspires.

What critics of turbo-folk fail to acknowledge is that inside this ‘corrupted’ cultural concept there is space for asserting multiple – and often conflicting – ideas and practices. Analyzing the case of an ex-Muslim turbo-folk star Sinan Sakic in his article for Belgrade’s NIN (2006), journalist Zoran Cirjakovic reflects on the ‘Orientalist’ culture discourse of today’s liberal Serbia, emphasizing complex and sometimes controversial roles that turbo-folk artists can maintain in different socio-political environments. Sakic is simultaneously dismissed both by Serbian liberal circles and the Bosnian Islamists – by the former for being too Oriental and Islamist, and by the latter for being too liberal and essentially anti-Islamic. Describing the diversity of Sakic’s audience at a concert at Belgrade’s ‘Tasmajdan’, Cirjakovic finds in turbo-folk the expressions of multi-ethnical and multicultural tolerance – the very same values to which Serbia’s liberal elite aspires.

On the other hand, in her performance This is Contemporary Art, staged in Vienna in 2001 (with singer Dragana Mirkovic in the leading role), Serbian artist Milica Tomic dislocates turbo-folk from its status as a local genre to the larger international art scene, stressing how the music ‘has paved a way for globalization to enter isolated and excluded Serbia’.

On the other hand, in her performance This is Contemporary Art, staged in Vienna in 2001 (with singer Dragana Mirkovic in the leading role), Serbian artist Milica Tomic dislocates turbo-folk from its status as a local genre to the larger international art scene, stressing how the music ‘has paved a way for globalization to enter isolated and excluded Serbia’.

Apart from renegotiating the dominant cultural narratives, Tomic’s performance presented turbo-folk’s potential for inter-cultural dialogue – an event which provided a rare occasion for Serbia’s diaspora in Vienna to ‘become visible in Austrian public life’.

However, turbo-folk’s capacity for asserting disparate and ‘subversive’ values was probably best captured by turbo-folk itself. Commenting on violence during last year’s Belgrade Gay Pride, Ceca’s unofficial successor, Jelena Karleusa, surprised everyone when she publicly denounced both the discourses of homophobia and Serbian nationalism in columns written for daily tabloid Kurir. The fact that a turbo-folk star – and an icon for Serbia’s transgender population, for that matter – would write a series of articles infused with liberal and anti-nationalist ideas might come as a surprise, but Karleusa’s subsequent discussion with members of the Serbian liberal elite in a prime-time political talk show made her into everyone’s favorite guilty pleasure. It further underpinned turbo-folk’s peculiar position in Serbian culture today, as being at the same time the dominant mainstream and its own hidden subversion.

More than a decade after the political changes of 2000, the notorious music genre that became synonymous with the former nationalist regime in Serbia has anything but disappeared. Turbo-folk continues to play the role of both hero and villain – it is the best known Serbian ‘brand’ and, at the same time, the skeleton in its closet. Typically labeled as a form of Oriental backwardness, it is likewise regarded as a feature of westernization, trans-balkanism and globalization. Seen through the spectacles of feminist critique, it bounces back as a transgender subversion. When defined as the encompassing mainstream of Serbian culture, it appears simultaneously as its obscene undertext, hidden in underground clubs virtually absent from the mass media.

The multiple layers of meaning inscribed in turbo-folk today imply a necessary re-evaluation of the existing paradigms that regard it solely as the cultural embodiment of Serbian nationalist-authoritarianism. Its continuing vitality, and, above all, its alignment with the zeitgeist, might not entirely be fault of the now-deposed regime. Ceca may be under house arrest, but even before she struck her deal with the prosecutors, a new league of celebrities and ‘erotic queens’ had already taken the stage to replace her. And the picture looks oddly familiar. Along with the steady resurgence of extremist nationalism, one might think that Serbia is still living its turbo-folk.

Originally published by Institute for Human Sciences, Vienna (IWM)