Praised for its gastronomical and allegedly healing qualities, the famous Balkan dish is simultaneously seasonal, historic, local and of course, even a bit macho

Anybody who has been to the United States recently (or watched the Portlandia skit making fun of overzealous picklers) knows that pickles are all the rage among the hipster masses of Portland and beyond. Part of the (largely appallingly apolitical) foodie trend that is sweeping the nation’s more privileged pantries, pickles are part of the hip, new American kitchen – nice to look at, good to post pictures of on Facebook, less appealing to eat every day (that’s what kale and avocados and sushi are for). But anyone who has ever been to the Balkans knows that the cute, hand-painted jars of colorful pickled beets and corn bejewelling Brooklyn larders have got nothing on their southeastern European counterpart: Meet kiseli kupus, aka whole pickled cabbage heads, aka the Balkan hard-core pickle.

Kiseli kupus is a staple of the Balkan winter. Walking into a building in the frostier months, you’re likely to encounter, in addition to the familiar smell of cigarette smoke, a strangely pungent odor wafting out of the basements and kitchens – the smell of whole pickled cabbage heads. Now, admittedly, this isn’t the most intuitively alluring of scents, but behind it lies the story of a food that is simultaneously seasonal, historic, local, and yes, even macho.

Kiseli kupus is prepared through the lacto-fermentation of whole heads of cabbage, which means that no vinegar or boiling is required. Instead, people pack large plastic barrels with cabbages, cover them in a mixture of water and salt, and leave this to ferment for a couple of months. To prevent the salt from settling, short hoses are attached to the bottom of the barrel and vigorously blown into every few days. Think of blowing bubbles into milk with a straw. Except with fermented cabbage juice.

Pickling is still often done in family homes, even in the apartment buildings of cities like Belgrade and Zagreb, and it’s often a whole-family endeavour. In a region more known for its patriarchal ways than its feminist politics, the making of kiseli kupus is a delightfully gender inclusive affair. Perhaps it’s because it entails heavy lifting (one family will easily make over 100 pounds worth of kiseli kupus in a season), or maybe it’s because it provides an excuse to take power tools to vegetables (see the illuminating YouTube clip below). Whatever it is, men often take pride in their pickling abilities.

After a few months of fermentation, the kiseli kupus is ready to use. Its flavor is similar to sauerkraut, but more mellow and buttery, with a firm crunch to the leaves. It can be eaten raw as a salad, baked with sausages, or used to make the region’s most iconic winter dish: sarma. Sarma, is made by wrapping some combination of ground meat, rice, onions, and garlic in leaves of kiseli kupus, and simmering it for hours, or long enough so that the scent spreads and everyone within a two-block radius becomes aware of the impending meal. People in the Balkans wax poetic about the dish, and it’s widely recognized that a good sarma is only as good as the cabbage that went into its making.

The gustatory pleasures of kiseli kupus aside, this Balkan pickle is also widely lauded for its health benefits. People often boast that there is no better source of vitamin C to be found, and an article published in a scientific journal on microbiology in 1962 praised the “Yugoslavian pickled cabbage” for its high levels of ascorbic acid. In addition to its scurvy-slaying powers, kiseli kupus is also responsible for one of this alcohol-steeped region’s favorite hangover cures: rasol. Rasol is, essentially, the raw brine in which the cabbages pickle. With its somewhat snotty green color and jarring smell, this may not seem like the most intuitive thing to reach for on those repentant Sunday mornings after a few too many shots of rakija, but people who have tried rasol swear up and down about its curative properties.

There is a cost to the tasty and healing qualities of kiseli kupus, however. In the Spring, the dreaded time to dispose of the gallons of leftover brine arrives. After months of fermentation, the smell of the resultant liquid can better be described by anecdote than adjective. Hyperbolic stories abound: some pour it down the nearest sewer grate late at night when neighbors are asleep, so as not to be associated with the stink that would haunt the corner for the ensuing day; Others override the rasol smell by putting cigarette butts up their noses. Whichever way it’s done, disposing of kiseli kupus brine requires multiple people, and what better way to bond than over the wastewater of pickled cabbage?

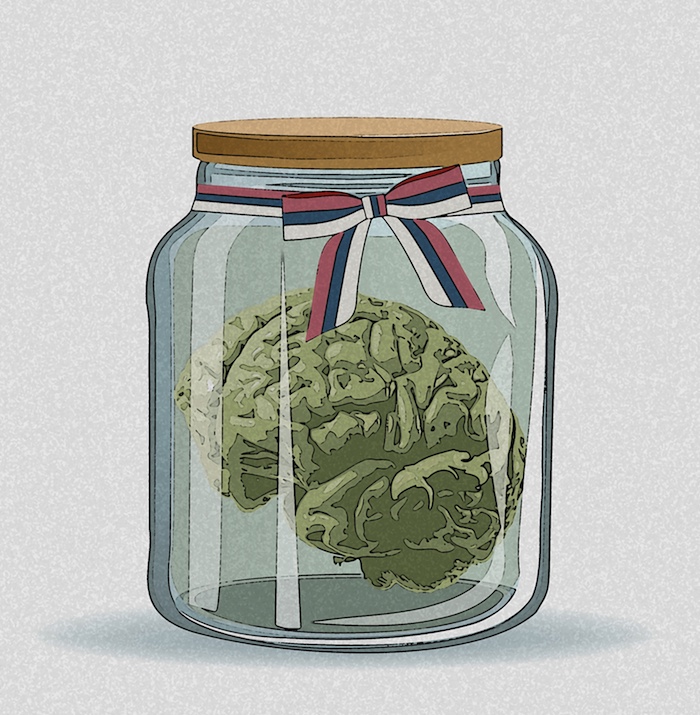

So why hasn’t kiseli kupus made it to North America’s hipster foodie pantries and menus yet? Perhaps it’s the smell, or maybe it’s the time commitment, or maybe it’s the fact that when placed in glass jars, whole pickled cabbage heads bear a more striking resemblance to a formaldehyde-steeped brain than to a regional delicacy. Whatever it is, people in the Balkans were pickling whole heads of cabbage before pickling became cool, and if the smell of winter kitchens is any indication, they’re not about to stop anytime soon. Sarma time.

Tiana Bakić Hayden is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at New York University. She does research on street food and informal economies in Mexico, the Balkans, and beyond.